Crisis management in the age of extreme uncertainty

11 August 2020 — It is still too early to say who is right and wrong in the aftermath of COVID-19, but the pandemic provides a unique opportunity to analyze the dynamics that influence how nations respond to a common threat. In this article, we provide an in-depth analysis of how Vietnam handled the first wave of the pandemic and propose a framework for business leaders to draft a crisis response and enhance their organization’s resilience in a crisis.

Problem

COVID-19 has put many countries under unprecedented crisis and pressured national leaders to make decisions under extreme uncertainty and empirical data scarcity. Vietnamese leaders, in contrast with those of other countries, have responded drastically and decisively despite a lower number of cases and lack of information in the early stage.

Why it happens?

Why nations respond very differently to crisis can be explained with Jared Diamond’s 12-factor framework. [1] Vietnam’s reactions can be attributed to an early acknowledgement of crisis and ultra-realistic self-appraisals of the public health capacity supported by other preconditions such as experience with previous crisis and national values.

Solution

There are patterns in national responses to crises that business leaders can learn from to manage corporate crises. Though crises tend to be unexpected and involve lots of uncertainty, there are aspects that are still in leaders’ control that can positively influence the outcome. However, corporate leaders may need to make extra efforts in regularly strengthening the preconditions to increase their company’s resilience and readiness to overcome crisis.

Download this post (PDF)

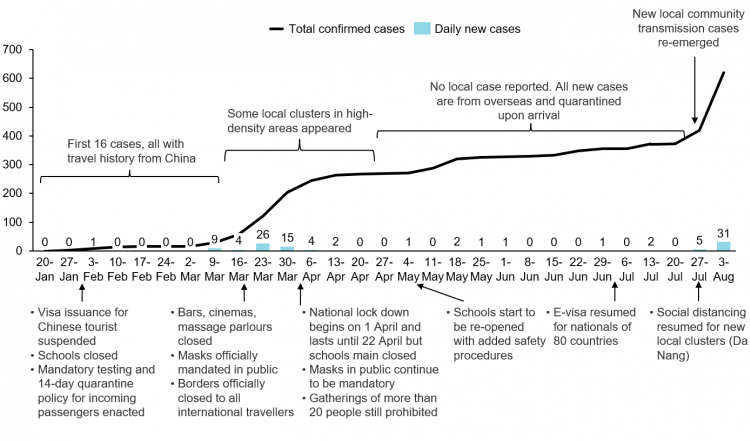

At the time of writing, Vietnam is entering the second wave of the pandemic after new local community transmission cases were detected again on 25 July 2020 after more than three months free of local cases. It remains to be seen how Vietnam will come out of the second phase as the number of confirmed cases has risen steeply to 652 on 3 August from just 417 a week ago.[2] However, the story of how Vietnam responded and managed to contain the first wave of the pandemic brings forth interesting lessons on crisis management for business leaders, especially when analyzed in contrast with other countries. The wide spread of the pandemic is unfortunate but provides such a unique opportunity to analyze how countries respond to the same crisis in varying ways.

To understand the dynamics behind these different choices, Jared Diamond (2019)’s list of twelve factors that influence the approach and outcomes of national crises in his latest book Upheaval: Turning Points for Nations in Crisis provides a useful analytical framework. As Jared Diamond attempted to extend the understanding of how nations respond to crisis from the literature of individual crisis management, we posit that many of the lessons learned here can be applied to corporate crisis management with some modifications.

How nations respond to crisis is influenced by both historical and contemporary factors – some of which are more controllable than others

Before deep-diving into Vietnam’s COVID-19 case, let us first briefly understand Jared Diamond’s national crisis response mechanism. In addition, we propose some modifications to the framework to allow more structured retrospective analysis and for it to be a more useful tool to draw strategies for ongoing crises.

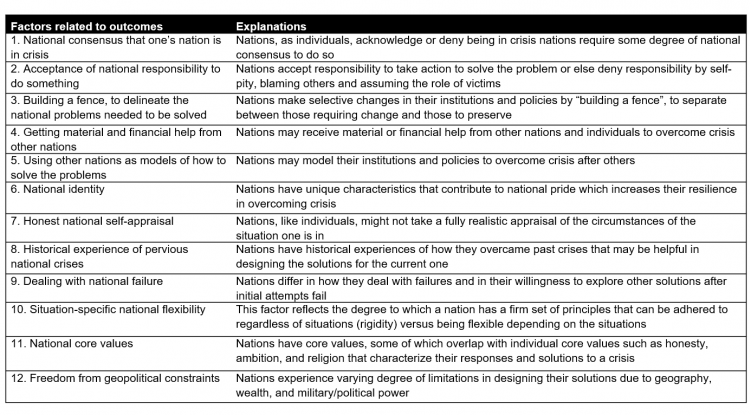

The central thesis of Jared Diamond’s book is that there are parallel dynamics that can be drawn from the wealth of literature on personal crisis to understand how nations overcome national crises – both those that occur abruptly as well as those that unfold gradually. He proposed twelve factors that dictate how a nation responds and ultimately emerges from national crises, which usually involve a set of choices that result in a different post-crisis status quo than the pre-crisis one. Some of these factors have a more straightforward parallel between individual and national crisis response mechanisms whereas some factors require some adjustments or are only applicable in the national context.

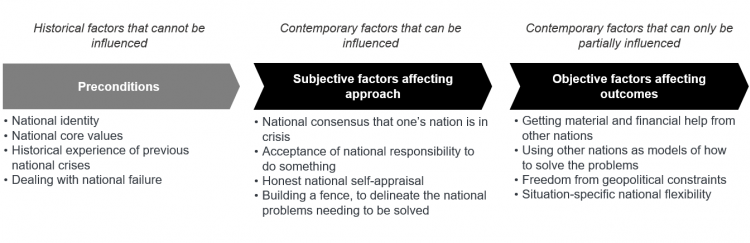

The list of the twelve factors above is re-produced and simplified from Jared Diamond’s (2019) original proposal, which can be further categorized to provide more structure and make it more as a live tool to design crisis response strategy. Although Jared Diamond already pointed out how these factors differ in terms of how closely related these are to individual crisis coping mechanism, we think that there are at least two other dimensions that differentiate these factors.

Firstly, some of these factors are historical which come as an endowment that accumulates over time or events that happened in the past. For these factors, or “preconditions”, such as national identity, core values, historical experiences, and attitude toward failure, contemporary leaders do not have much influence but can only be aware and learn to leverage those that are conducive to their crisis response strategy.

Secondly, for contemporary factors that are situation-specific, we can further divide them into those that are more in control of current national leaders such as creating a national consensus, taking responsibility, realistic assessment of current situations, and drafting a response strategy by segregating the problems that need to be solved. Besides these subjective factors, there are other ones that can only partially influenced by insiders as they require or depend on interactions with other nations such as getting help, having a model to take after, geopolitical constraints, and degrees of flexibility to take actions.

We believe that categorizing these factors into different categories with varying degrees of controllability can shed more light on the determining factors when analyzing a case retrospectively as well as serve as a framework to determine which factors that are at disposal for leaders to draft a response strategy in an ongoing crisis.

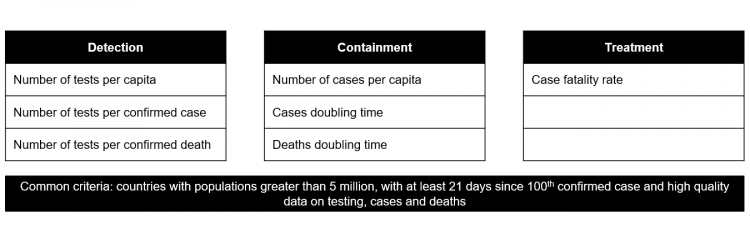

Vietnam selected as one of the few emerging success stories due to impressive detection and containment results

Based on available data on COVID-19 collected by Our World in Data database, experts at the Exemplars in Global Health (EGH) platform has selected Vietnam as one of the emerging COVID-19 success stories, alongside with South Korea and Germany.[3] Despite the data set being constantly updated, incomplete or incomparable, experts try to unify the criteria used to identify these success cases by leveraging seven indicators across three dimensions: detection, containment, and treatment.

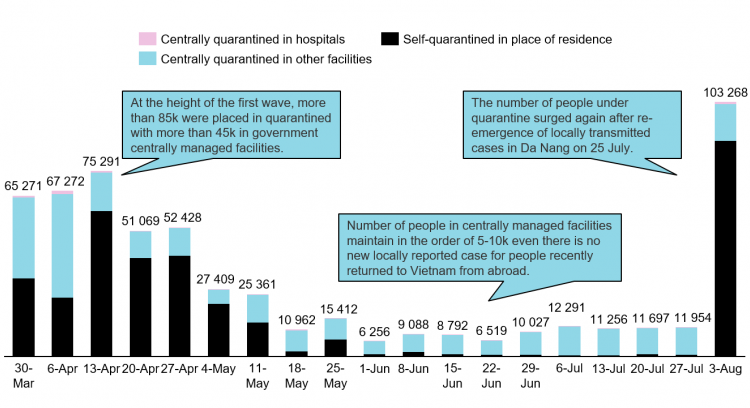

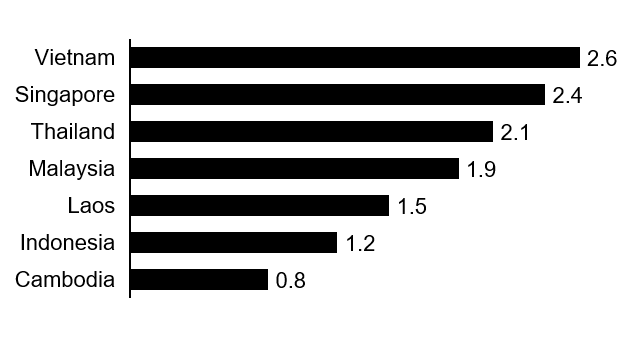

Based on the above criteria, Vietnam stands out, even among the success cases, especially in the detection and containment dimension with zero death at the time of analysis (end of June) although the number of fatality has increased to 8 as of 6 August as the second wave hits the country. In terms of detection, due to limited infrastructure, instead of mass testing as in South Korea, Vietnam implemented a targeted testing strategy for people who come in direct or indirect contact with every single case confirmed. This explains Vietnam’s significant high number of tests per confirmed case, at 967 tests per confirmed case as of 29 April 2020, compared to 60 in South Korea and 19 in Germany in around the same period. This targeted testing strategy is only possible thanks to a blanket approach to contact tracing, tracking to the third degree of contact (F1-F3) to the original case (F0). After being identified, these cases are sorted, tested, then placed in different quarantine policies ranging from institutionalized isolation (F1) to self-isolation under local supervision (F2-F3). [4]

Due to this systematic testing and quarantine procedure, there are at least 5 000 to 10 000 people in centralized quarantine facilities at any point in time, which even went up to nearly 50 000 at the height of the first wave in mid-April. As a result, the number of cases is extremely low, under 400 with no new locally transmitted case detected for three months up until late July when new local cases re-emerged again. This achievement is extraordinary for a country of more than 90 million, with proximity and close trade ties with China.

Both historical and contemporary factors play a role in Vietnam’s success in containing COVID-19

For achieving these results, the Vietnamese government can be credited for its swift, decisive, and expansive containment actions, including mobility restrictions, community mitigation, and surveillance in the very early stages when the number of cases was still well under 50. [4] In our opinion, this is possible due to two determining factors: the ability of the government to consistently create a national consensus and an ultra-realistic assessment of its public healthcare capabilities. In addition to these two contemporary and subjective factors, there are favorable historical factors such as previous experience with similar outbreaks and national pride as well as objective factors such as help and models from other nations that contribute to the success.

The fact that Vietnam closed all schools and enacted a mandatory 14-day quarantine for incoming passengers in government-run facilities on 30-31 January 2020 when the number of confirmed cases was just five – all are imported cases with travel histories from China – shows how much political will the Vietnamese government had in containing the infection before it went out of hand. To put things into perspective, most countries closed schools when the number of confirmed cases was at least 300. [6] Finland closed schools on 16 March when the number of cases were 272 [7], South Korea selectively at 500 [8] and Germany at 3000 [9]. While a mandatory 14-day quarantine policy for incoming travelers is still in effect, schools were re-opened on 4 May after three months when the number of confirmed cases stabilized at under 300. Given that both school closure and centrally managed quarantine policies are two of the most disruptive and controversial social distancing interventions, being able to maintain these measures given such a low number of cases demonstrated a high level of national consensus.

Some might disregard this achievement as an obvious consequence of the one-party political environment, which is used to receiving and executing orders rather than achieving consensus. However, a survey in late March found that 62% of people approved the level of intervention of the government, higher than any other 45 countries surveyed by the same public opinion research firm. [10] The government was able to achieve this through a concerted effort in communications through multiple channels with repetitive, consistent, and sometimes creative messages.

In addition to national consensus, another factor that enables the country leaders to enact such a disruptive intervention so early is an extremely realistic appraisal of the country’s public healthcare infrastructure. This honest appraisal is more interesting, considering that if we look at official numbers, Vietnam has one of the best ratios of hospital beds per 1 000 capita in the region.[11] However, local healthcare experts and country leaders know very well that current utilization is extremely unevenly distributed with centrally managed hospitals experiencing the worst overload due to low trust in the quality of lower-level local healthcare facilities. Knowing the importance of intensive care units (ICU) in treating the most severe COVID-19 patients, which are most available in already heavily overloaded centrally managed hospitals, it is understandable why Vietnamese leaders had to react in such a decisive way when the number of confirmed cases is still very low. This is one of the occasions when it is much better safe than sorry.

At the same time, there are other favorable historical and external factors that contribute to the effectiveness of the measures taken in Vietnam. For example, Vietnam was the first country to declare herself SARS-free in 2003. Such success in the past gave Vietnamese healthcare experts both the experience and confidence in making important recommendations to public policies when empirical data was still scarce and WHO recommendations were inconclusive. However, that past success was not achieved without a price as except for the index patient, all deaths during SARS 2003-2004 in Vietnam were healthcare professionals. Such a failure in protecting healthcare professionals during an infectious disease outbreak has led to significant investment to improve hospital infection control in the past decade.[4]

In addition, Vietnam also benefited from being one of the focus countries in close partnership with the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC experts have been providing the Vietnamese public healthcare system with technical assistance to strengthen its laboratories, surveillance, and workforce capacity to respond to infectious disease outbreaks since 1998. Together with WHO, CDC experts have helped Vietnam to set up a network of emergency operations centers with “disease detectives” to run exercises and trainings for key government stakeholders in case of outbreaks.[12] The accumulation of experience and preparedness culminated into the level of readiness of the Vietnamese public health systems to accommodate the requirements of the ongoing crisis.

Furthermore, Vietnam’s turbulent history has boosted the people’s solidarity especially under hardship and built a nationwide culture of accepting self-containment measures in times of difficulty. To this end, Vietnamese leaders have leveraged this well by consistently comparing the efforts to contain COVID-19 to a battle against invading enemies – a narrative very commonly known to generations of Vietnamese during and since the Vietnam war.

Unlike nations, corporate leaders need to consciously cultivate some of the pre-conditions for crisis readiness

As we have seen, individual crisis coping mechanism can be very well applied to understand and inform how nations can successfully emerge from a national crisis with some modifications. In the same manner, we believe that the same framework can be used as a tool for corporate leaders to assess the levers they have at their disposal to draft a corporate crisis response strategy.

However, while many of the contemporary factors are similar between national and corporate crises, we think that many of the preconditions which can be taken for granted for nations have to be consciously cultivated in the business environment. For example, factors such as national identity and core values might be more naturally ingrained among citizens than corporate identity and values among employees. Furthermore, in lieu of history lessons that institutionalize lessons learnt from previous crises and failures into the common consciousness of a society, corporate leaders need to be proactive in coordinating, distributing, and implementing lessons learnt from past and current upheavals in the companies’ operations to benefit from the same level of crisis preparedness. This is easier said than done as it is often very tempting for executives and middle managers to focus on executing current strategy rather than paying sufficient attention to prepare the company for crisis when the times are good.

If there is one important lesson learned to take away from the Vietnam COVID-19 story in the first wave, it is that preparing for a crisis started way before the very first case was confirmed.

References

[1] Diamond, Jared (2019), “Upheaval: Turning points for Nations in Crisis”, Boston, Little, Brown and Company.

[2] Wordometers (2020), COVID-19 data, retrieved at https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/viet-nam/ on 3 August 2020.

[3] Kenedy, D. et. al. (2020), “How experts use data to identify emerging COVID-19 success stories”, retrieved at https://ourworldindata.org/identify-covid-exemplars on 30 June 2020.

[4] Pollack, T. et. al. (2020), “Emerging COVID-19 success story: Vietnam’s commitment to containment”, retrieved at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-vietnam on 30 June 2020.

[5] Reddal consolidation from the Vietnamese Ministry of Health COVID-19 website, accessible at https://ncov.moh.gov.vn/ on 3 August 2020.

[6] Brahma, D. et. al. (2020), “The early days of a global pandemic: A timeline of COVID-19 spread and government interventions”, retrieved at https://www.brookings.edu/2020/04/02/the-early-days-of-a-global-pandemic-a-timeline-of-covid-19-spread-and-government-interventions/ on 2 April 2020.

[7] Yle (2020), “Finland closes schools, declares state of emergency over coronavirus”, retrieved at https://yle.fi/uutiset/osasto/news/finland_closes_schools_declares_state_of_emergency_over_coronavirus/11260062 on 3 August 2020.

[8] Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention, retrieved at https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501000000&bid=0015 on 6 August 2020.

[9] US News (2020), “Germany to shut most schools to slow coronavirus spread”, retrieved at https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2020-03-13/german-state-of-bavaria-closes-schools-to-slow-coronavirus-epidemic-dpa on 03 August 2020.

[10] Dölitzsch C. (2020), “Global study about COVID-19: Dalia assesses how the world ranks their governments’ response to the pandemic”, retrieved at https://daliaresearch.com/blog/dalia-assesses-how-the-world-ranks-their-governments-response-to-covid-19/ on 28 May 2020.

[11] World Bank, retrieved at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS on 3 August 2020.

[12] US Center for Disease Control and Prevention, retrieved at https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/countries/vietnam/default.htm#:~:text=CDC%20works%20closely%20with%20Vietnam,to%20respond%20to%20disease%20outbreaks. on 3 August 2020.

Tags

Vietnam, South-East Asia, Crisis management, COVID-19, Pandemic, Framework, National crisis, Crisis response, Leadership, Corporate culture, Corporate values, Crisis preparedness, Corporate crisis response strategy